11. For Loops¶

In the last chapter, we added the if statement

to our skill set, enabling the computer to choose which

set of code to run. In this chapter we learn how to loop.

Rather than have our programs run straight though, we

can run a section of code however many times we like.

This chapter covers for loops which allow us to loop a certain

number of times. The next chapter covers while loops which will loop

until a certain condition (such as game over) occurs.

11.1. Introduction to Looping¶

Most games loop. Most programs of any kind loop. Take for example a simple number guessing game. The computer thinks of a number from 1 to 100, and the player tries to guess it.

This is an easy game to program on the computer using

loops. Start with code that will take in a guess from the

user, and then tell the user if they are too high, too low, or

correct using the if statements we learned about in

the last chapter. Then, we just need to loop that code until

the user guess correctly, or runs out of guesses.

Here’s an example run of just such a program:

Hi! I'm thinking of a random number between 1 and 100.

--- Attempt 1

Guess what number I am thinking of: 50

Too high.

--- Attempt 2

Guess what number I am thinking of: 25

Too high.

--- Attempt 3

Guess what number I am thinking of: 17

Too high.

--- Attempt 4

Guess what number I am thinking of: 9

Too low.

--- Attempt 5

Guess what number I am thinking of: 14

Too high.

--- Attempt 6

Guess what number I am thinking of: 12

Too high.

--- Attempt 7

Guess what number I am thinking of: 10

Too low.

Aw, you ran out of tries. The number was 11.

(The code for this program: Number Guessing Game Example)

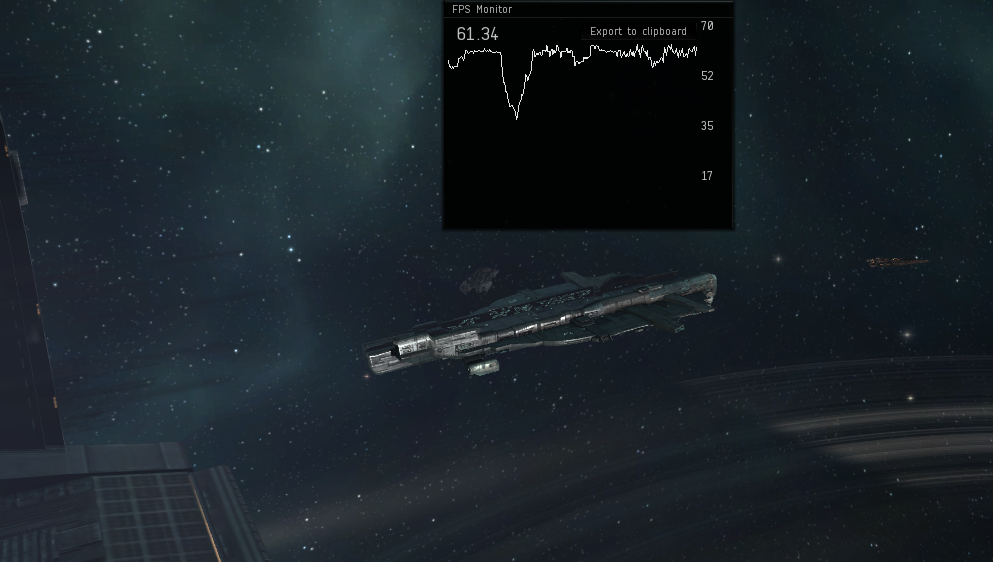

Wait, what does this simple text game have to do with advanced graphical games? A lot. You may be familiar with the frames-per-second (FPS) statistic that games show. The FPS represents the number of times the computer updates the screen each second. Each frame in a video game is one time through a loop. The higher the rate, the smoother the game. (Although an FPS rate past 60 is faster than most screens can update, so there’s not much point to go faster.) The figure below shows the game Eve Online and a graph showing how many frames per second the computer displaying.

FPS in video games¶

The loop in these games works like the flowchart this figure:

Game loop¶

The inside of these loops have three common steps:

Get user input.

Perform calculations.

Output the result.

Then we loop this 60 times per second until the user asks to close the program.

There can even be loops inside of loops. Take a look at the “Draw Everything Loop” flowchart below. This set of code loops through and draws each object in the game. You can put this loop inside the larger loop that draws each frame of the game.

Draw Everything Loop¶

There are two major types of loops in Python, for loops and while

loops. If you want to repeat a certain number of times, use a for loop. If

you want to repeat until something happens (like the user hits the quit button)

then use a while loop.

For example, a for loop can be used to print all student records, since the

computer knows how many students there are. We could wait for the user to click

the mouse button with a while loop, because we don’t know how many times

we’ll have to loop before that happens.

11.2. For Loops¶

This for loop example runs the print statement five times. It could

just as easily run 100 or 1,000,000 times by changing the 5 to the desired

number. Note the similarities of how the for loop is written

to the if statement. Both end in a colon, and both use indentation to specify

which lines are affected by the statement.

1 2 | for i in range(5):

print("I will not chew gum in class.")

|

Go ahead and enter it into the computer. You should get output like this. Try adjusting the number of times that it loops.

I will not chew gum in class.

I will not chew gum in class.

I will not chew gum in class.

I will not chew gum in class.

I will not chew gum in class.

The i on line 1 is a variable that keeps track of how many times the program has

looped, sometimes called the counter variable.

It is a regular variable, and can be named any legal variable name.

Programmers sometimes use i as for the variable name, because the i is short for

increment and that’s often what the variable does.

This variable helps track when the loop should end.

The range function controls how many times the code in the loop is run.

In this case, five times.

The next example code will print “Please,” five times and “Can I go to the

mall?” only once. “Can I go to the mall?” is not indented so it is not part of

the for loop and will not print until the for loop completes.

1 2 3 | for i in range(5):

print("Please,")

print("Can I go to the mall?")

|

Go ahead and enter the code and verify its output.

Please,

Please,

Please,

Please,

Please,

Can I go to the mall?

This next code example takes the prior example and indents line 3. This change

will cause the program to print both “Please,” and “Can I go to the mall?” five

times. Since the statement has been indented “Can I go to the mall?” is now

part of the for loop and will repeat five times just like the word “Please,”.

1 2 3 | for i in range(5):

print("Please,")

print("Can I go to the mall?")

|

Here’s the output of that program:

Please,

Can I go to the mall?

Please,

Can I go to the mall?

Please,

Can I go to the mall?

Please,

Can I go to the mall?

Please,

Can I go to the mall?

You aren’t stuck using a specific number with the range function. This

next example asks the user how many times to print using the input function

we talked about last chapter in The input Function. Go ahead and try the

program out.

1 2 3 4 5 6 | # Ask the user how many times to print

repetitions = int(input("How many times should I repeat? "))

# Loop that many times

for i in range(repetitions):

print("I will not chew gum in class.")

|

You could also use what we learned about functions, and take in the value by a parameter as shown in this example:

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 | def print_about_gum(repetitions):

# Loop that many times

for i in range(repetitions):

print("I will not chew gum in class.")

def main():

print_about_gum(10)

main()

|

11.2.1. Using the Counter Variable¶

You can use the counter variable in the for loop to track

your loop. Try running this code, which prints the value stored in i.

1 2 | for i in range(10):

print(i)

|

With a range of 10, you might expect that the code prints the numbers 1 to 10.

It doesn’t. It prints the numbers 0 to 9.

It is natural to assume that range(10) would include 10, but it doesn’t.

0

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

In computer programming, we typically start counting at zero rather than one. Most computer languages use this convention. An old computer joke is to get your friend a mug that says “World’s #1 programmer.” Then get yourself a mug that says “World’s #0 programmer.”

If a programmer wants to go from 1 to 10 instead of 0 to 9, there are a couple

ways to do it. The first way is to send the range function two numbers instead

of one. The first number is the starting value, the second value we’ll count up

to, but not equal to. Here’s an example:

1 2 | for i in range(1, 11):

print(i)

|

Give it a try. It should print the numbers 1 to 10 like so.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

It does take some practice to get used to the idea that the for loop will include the first number, but will not include the second. The example specifies a range of (1, 11), and the numbers 1 to 10 are printed. The starting number 1 is included, but not the ending number of 11.

Another way to print the numbers 1 to 10 is to still use range(10) and

have the variable i go from 0 to 9. But just before printing out the variable,

add one to it. This also works to print the numbers 1 to 10, as shown in our next

example.

1 2 3 4 | # Print the numbers 1 to 10.

for i in range(10):

# Add one to i, just before printing

print(i + 1)

|

11.2.2. Counting By Numbers Other Than One¶

If the program needs to count by 2’s or use some other increment, that is easy.

Just like before there are two ways to do it. The easiest is to supply a third

number to the range function that tells it to count by 2’s.

See this code example:

1 2 3 | # One way to print the even numbers 2 to 10

for i in range(2, 12, 2):

print(i)

|

The second way to do it is to go ahead and count by 1’s, but multiply the variable by 2 as shown in the next example.

1 2 3 | # Another way to print the numbers 2 to 10

for i in range(5):

print((i + 1) * 2)

|

Both examples will output the numbers 2 to 10:

2

4

6

8

10

It is also possible to count backwards–for example 10 down to zero.

This is done by giving the range

function a negative step. In the example below we start at 10 and go down to, but not

including, zero. (To include zero, the second number would need to be a -1.)

We do this by an increment of -1.

1 2 | for i in range(10, 0, -1):

print(i)

|

The hardest part of creating these backwards-counting loops is to accidentally

switch the start and end numbers.

Normal for loops that count up start with the smallest value.

When you count down the program starts at the largest value.

Output:

10

9

8

7

6

5

4

3

2

1

If the numbers that a program needs to iterate through don’t form an easy pattern, it is possible to pull numbers out of a list as shown in the next example. A full discussion of lists will be covered in the Introduction to Lists chapter.

1 2 | for item in [2, 6, 4, 2, 4, 6, 7, 4]:

print(item)

|

This prints:

2

6

4

2

4

6

7

4

11.3. Nesting Loops¶

By nesting one loop inside another loop, we can expand our processing beyond one dimension.

Try to predict what the following code, which is not nested, will print. Then enter the code and see if you are correct.

1 2 3 4 5 | # What does this print? Why?

for i in range(3):

print("a")

for j in range(3):

print("b")

|

Did you guess right? It will print three a’s and 3 b’s.

This next block of code is almost identical to the one above. The second for

loop has been indented one tab stop so that it is now nested inside of the

first for loop. It is a nested loop.

This changes how the code runs significantly. Look at it and see if you can

guess how the output will change.

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 | # What does this print? Why?

for i in range(3):

print("a")

for j in range(3):

print("b")

print("Done")

|

Did you guess right? We still get three a’s, but now we get nine b’s.

For each a, we get three b’s.

The outside for loop causes the inside code to be run three times.

The inside for loop causes its code to be run three times, so three

times three is a total of nine times to run the innermost code.

Complicated? Not really. You’ve already lived a loop like this. This is how a clock works. The 1-12 hour is the outside loop, and the 0-59 minute is the inside loop. Try this next example and see now it prints all the times between 1:00 and 12:59. (Later on in Clock Example with Leading Zeros we’ll show how to format the output and make it look good.)

1 2 3 4 | # Loop from 1:00 to 12:59

for hour in range(1, 13):

for minute in range(60):

print(hour, minute)

|

11.4. Keep a Running Total¶

A common operation in working with loops is to keep a running total. This “running total” code pattern is used a lot in this book. Keep a running total of a score, total a person’s account transactions, use a total to find an average, etc. You might want to bookmark this code listing because we’ll refer back to it several times. In the code below, the user enters five numbers and the code totals up their values.

1 2 3 4 5 | total = 0

for i in range(5):

new_number = int(input("Enter a number: " ))

total = total + new_number

print("The total is: ", total)

|

Note that line 1 creates the variable total, and sets it to an initial amount

of zero. It is easy to forget the need to create and initialize the variable to

zero. Without it the computer will complain when it hits line 4. It doesn’t

know how to add new_number to total because total hasn’t been given

a value yet.

A common mistake is to use i to total instead of new_number. Remember,

we are keeping a running total of the values entered by the user, not a running

total of the current loop count.

Speaking of the current loop count, we can use the loop count value to solve some mathematical operations. For example check out this summation equation:

If you aren’t familiar with this type of formula, it is just a fancy way of stating this addition problem:

The code below finds the answer to this equation by adding all the numbers from 1 to 100. It is another demonstration of a running total is kept inside of a loop.

1 2 3 4 5 | # What is the value of sum?

total = 0

for i in range(1, 101):

total = total + i

print(total)

|

Here’s yet another example of keeping a running total.

In this case we add in an if statement.

We take five numbers from the user and count

the number of times the user enters a zero:

1 2 3 4 5 6 | total = 0

for i in range(5):

new_number = int(input( "Enter a number: "))

if new_number == 0:

total += 1

print("You entered a total of", total, "zeros")

|

11.5. Review¶

In this chapter we talked about looping and how to use for loops

to count up or down by any number.

We learned how loops can be nested. We learned how we can use a loop

to keep a running total.

11.5.1. Review Questions¶

Open up an empty file and practice writing code that use for loops to:

Print “Hi” 10 times.

Print ‘Hello’ 5 times and ‘There’ once

Print ‘Hello’ and ‘There’ 5 times, on different lines

Print the numbers 0 to 9

Two ways to print the numbers 1 to 10

Two ways to print the even numbers 2 to 10

Count down from 10 down to 1 (not zero)

Print numbers out of a list

Answer the following:

What does this print? Why?

for i in range(3):

print("a")

for j in range(3):

print("b")

What is the value of a?

a = 0

for i in range(10):

a = a + 1

print(a)

What is the value of a?

a = 0

for i in range(10):

a = a + 1

for j in range(10):

a = a + 1

print(a)

What is the value of a?

a = 0

for i in range(10):

a = a + 1

for j in range(10):

a = a + 1

print(a)

What is the value of sum?

total = 0

for i in range(1, 101):

total = total + i

11.5.2. On-line Review Problems¶

Practice on-line by completing the for loop problems starting with 04 available here: